By Ralph Winter

One of our recent publications states the following for the general public:

We’re glad you’re here! Our purpose in meeting each Thursday night is to celebrate what God is doing around the world and to learn how we can better participate in His purposes for the nations. In particular, we come to give special attention to frontier mission among 10,000 unreached peoples without strong, culturally relevant church movements in their midst. Let’s seek God together for how we should respond to what we hear.

Note the fact that the phrase by itself, Unreached Peoples, could easily be misunderstood by visitors apart from the additional defining phrase, “without strong, culturally relevant church movements in their midst.” It is very good for that to be added. The need for that additional phrase, incidentally, explains why, as an institution, we had earlier objected to the phrase, Unreached Peoples, preferring our own phrase, Hidden Peoples,as well as a different definition.

Thus, I approve of the helpful “appositional” phrase that explains to the general public very accurately what Unreached Peoples means to us.

Here is a statement from another document that attempts to state what we are all about:

The over-arching vision within the Frontier Mission Fellowship group of projects is to see all unreached peoples reached with the gospel and the kingdom to come among them. In evangelical terms we would know when a group was reached when there was an indigenous church planting movement among them.

I would like to see if we can go beyond these statements to something more.

If we think of the remaining unreached peoples as enemy occupied territories, rather than merely unenlightened areas, “reaching” them with “a viable, evangelizing, indigenous church movement” could seem to assume the possibility that the problem of unreached peoples is merely the absence of good news.

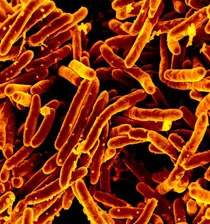

I continue to believe that “reaching unreached peoples” with a viable, evangelizing, indigenous church movement is a most worthy and important thing to do. However, it may involve unexpected, perplexing opposition and danger. In that case is it fair to prospective missionaries to talk as though it is merely a communication problem? And, is it fair to the people within the group we are trying to reach, for them to think that we see no use for the significant knowledge we in fact possess that could enable many of them not to be become victims of disease?

Otherwise it would seem to be sort of like telling willing recruits that they need merely to walk into Falouja thinking that the only thing they need to do is inform the people that democracy is the answer to all their problems. In other words after we make the missiological breakthrough and see a people movement to Christ, what do we do with the fact that most of the new believers will die very, very prematurely because of pathogens about which neither Jesus or Calvin said a word, but pathogens about which we now know a great deal?

...it would seem to be sort of like telling willing recruits that they need merely to walk into Falouja thinking that the only thing they need to do is inform the people that democracy is the answer to all their problems.

Jesus extensively demonstrated God's concern for the sick. Are we today under any obligation to demonstrate even more cogent ways of fighting off illness, due to the additional insight God has allowed us to gain? Or is it no longer important for people to know that sickness is very definitely a concern of God? Are those who hear our words and witness our work and our concerns supposed to think that our God is just the God of the next world?

This morning Gordon Kirk at Lake Avenue delivered a powerful sermon in effect galvanizing believers to shape up, quit quibbling over peripherals, regain their faith and joy and demonstrate unity. It was all to the good.

However, it was somewhat like giving a rousing charge during wartime to the individuals in an army to stop quarrelling, vying for leadership, grumbling, living with disunity in the ranks, etc. without mentioning the crucial additional truth that there is a war to fight. What unifies disparate, normally quarrelsome men is precisely the unity of fighting the same war. No wonder so many veterans groups emerge from a war, groups of men who are astoundingly disparate otherwise.

What unifies disparate, normally quarrelsome men is precisely the unity of fighting the same war.

Churches that are riven by internal disunity may often be plagued in part by the lack the unifying power of a significant external goal. Even if that goal is merely getting pamphlets to Iraq it will certainly help unify the church. However, if the goal is to confront a hideous, invisible enemy that has infiltrated the bloodstream of every member of the church and will be causing pain and suffering and premature death, that unity might come much more quickly and solidly.

I had similar concerns recently as I listened to Greg Livingstone share his experiences with several key Muslims who were apparently glad to talk to him but did not appear to be seeking God. They are Muslims, perhaps, only in the sense that they may be caught up in a cultural tradition they felt they could not abandon. I wonder what would have happened if he had shared with them his awe for the glory of God? How would he have done that and how would these men have reacted? Maybe their disinterest would have turned them away and he would then have had to spend time with others whose hearts toward God were more tender?

The average missionary in a Muslim village does not share with the people many similar goals. The one common denominator which might possibly draw both missionary and Muslim together could be to share, positively and humbly, genuine awe for the glory of God as seen in a microscope, and negatively, to share genuine awe and fear for the additional evidence in that same microscope of an intelligent, malicious enemy of them both. The missionary and the Muslim can both be awed (and worship) as they contemplate God's glory together, and they can together be gripped by the urgent, crucial task of fighting a common enemy that is constantly tearing down that glory. Isn’t that what Jesus' extensive healing ministry would teach us to do?